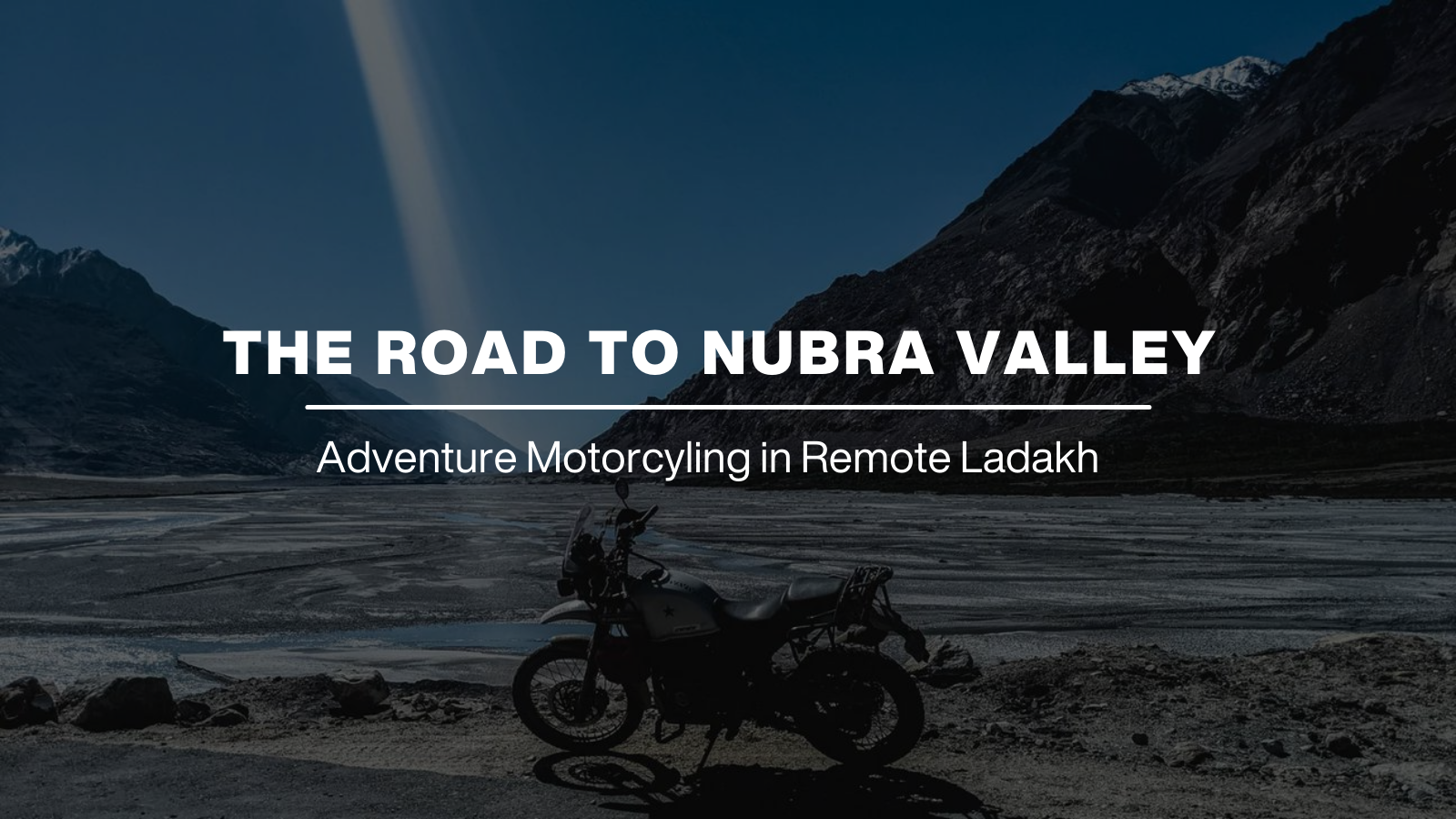

The Road to Nubra Valley, Ladakh- Volume I

Continuing our series on trip reporting from some of the most remote areas on the planet. Catch up on the first installment here.

After my ride to Hanle, it was time to head up north towards my next destination, the landscaped vistas of Nubra Valley. The valley lies in the northernmost part of Ladakh and I had visited it previously in 2016. I was keen to explore the last settlements of villages which are located along the Nubra and the Shyok rivers, and revisit the Hundar sand dunes. Situated about 150 km from Leh, Nubra Valley was originally called Ldumra which meant the valley of flowers. It is surrounded by snow capped Himalayan ranges, and lies sandwiched between Tibet and Kashmir bordering Baltistan controlled by Pakistan and Chinese Turkestan in the north, and the Aksai Chin plateau and Tibet in the east which is controlled by the Chinese. Apart from its scenic views, Nubra was also an important stopover on the ancient trade routes with Central Asia.

On day one, I started my journey from Leh which is the most common route taken to reach the valley, via the awe-inspiring Khardung La which is mostly open throughout the year. The elevation of Khardung La is 5,359 m (17,582 ft) and is just 40kms from Leh so people often chose to cycle or even hike to the pass from Leh. A trip to Ladakh isn’t complete without a visit to Khardung La as the views from the top are mesmerising and just the sheer altitude of the pass is enough bragging rights as it is. It’s usually thronged with motorcyclists at the top, but it’s also not advisable to stay there for long due to the high altitude. After stopping to take a few customary pictures at the top, I had crossed the pass by noon. My first stop was at the tiny village of North Pullu for a coffee where I got into a conversation with two locals who started giving me insights about the valley. They belonged to the village of Panamik and insisted that I visit Panamik on my ride. Thus, I headed towards the Nubra river side which is home to numerous villages, the famous Panamik hot springs, the village of Warshi and the Siachen Base Camp of the Indian Army at the Siachen Glacier.

The terrain is beautiful, and one gets to enjoy the twisty roads which are mostly well laid. At Khardung village I saw the starting point of the Khardung La challenge, one of the highest ultra marathons in the world. By 2 pm I reached Khalsar village, from where the fork in the road splits for Turtuk and Warshi. During my first visit to Nubra, this junction had only one shop which was a tire puncture shop and only one guy managing it all by himself in the middle of nowhere. He was extremely friendly and had helped us with our bikes the last time I was there, and I rode up to his tiny garage to see if he still managed the place. Funnily enough - he goes by the name of “Keval” which literally means “alone / only” in English. He invited me in for a tea and we spoke briefly, post which I carried on with my journey towards Warshi.

The terrain is beautiful, and one gets to enjoy the twisty roads which are mostly well laid. At Khardung village I saw the starting point of the Khardung La challenge, one of the highest ultra marathons in the world. By 2 pm I reached Khalsar village, from where the fork in the road splits for Turtuk and Warshi. During my first visit to Nubra, this junction had only one shop which was a tire puncture shop and only one guy managing it all by himself in the middle of nowhere. He was extremely friendly and had helped us with our bikes the last time I was there, and I rode up to his tiny garage to see if he still managed the place. Funnily enough - he goes by the name of “Keval” which literally means “alone / only” in English. He invited me in for a tea and we spoke briefly, post which I carried on with my journey towards Warshi.

It was easy riding alongside the Nubra river. The Border Roads Organisation has put up some witty and motivational sign posts all across Ladakh which are quite entertaining to read, cautioning travellers of over speeding. Tiny villages kept popping up with barely any other tourists as most of them head towards the valley on the side of the Shyok river. I had passed Panamik in no time, and I intended upon camping closer to Warshi - which was the last village on this side of the valley. It was tricky finding a good camping spot as it’s mostly a desert and I needed access to clean drinking water. I finally stopped near a store where the elderly store owner was within earshot and called out to him asking for a place to camp for the night.

It was easy riding alongside the Nubra river. The Border Roads Organisation has put up some witty and motivational sign posts all across Ladakh which are quite entertaining to read, cautioning travellers of over speeding. Tiny villages kept popping up with barely any other tourists as most of them head towards the valley on the side of the Shyok river. I had passed Panamik in no time, and I intended upon camping closer to Warshi - which was the last village on this side of the valley. It was tricky finding a good camping spot as it’s mostly a desert and I needed access to clean drinking water. I finally stopped near a store where the elderly store owner was within earshot and called out to him asking for a place to camp for the night.

Now here’s the thing about Ladakh - apart from the charming, diverse landscapes - the people of Ladakh are also the warmest, kindest and extremely helpful. The store owner gladly offered me a spot next to his store which was a tiny piece of land that he owned which was covered by trees for shade and surrounded by a fence for protection. It also had a tiny stream flowing through it with clean, drinking water. This was at a tiny village called Changlung, the total population of which consisted of about five families. We spoke at length about my travels, and life at the tiny village of Changlung. He told me about a hot spring at the village which was currently being used by the army to set up a laundry unit, but which provided an unlimited supply of hot water to all the households in the harsh winters. He got really fascinated by my portable butane gas stove that I used for cooking. I promised I would send one for him once I get back, although I’m yet to deliver on my promise. In hindsight, I should have probably left my stove with him but I guess I’ll just have to pay him another visit in the near future.

In the morning, I rode to Warshi village which was the last village to which tourists are generally given permission to travel. The road leads to the Siachen army base camp, the final frontier of the Indian Army at the actual line of control with the Chinese. 10 days after my visit to the Nubra Valley, the Indian government had allowed access to Siachen base camp for all tourists. It was a cruel joke played on me as I was quite keen on visiting the base camp. As I made my way back from Changlung, I rode up to the establishment of the famous Panamik hot springs. The sulphur-rich hot springs are said to contain medicinal properties. I had visited a few hot springs before this, but the best thing about this particular place was the setup at the springs which consisted of a mildly hot-water pool, with separate smaller pools of extremely hot water. One could pick and choose as per one’s preference of the water’s temperature. I promptly jumped into the pool for a refreshing bath, had lunch after which I headed towards the other side of the valley.

Share:

Best Christmas Albums for Opening Presents

The Ultimate Guide to Tinnitus